“In students’ eyes an important component of successful learning is perceiving the teacher as both ally and authority” (Brookfield, 2006, 67)

How and why does this relate to the roles of the practicing practitioner, teacher and artist? Draw from the readings set and in the weekly breakdown and bibliography to support your response.

Students need to feel comfortable around their teachers in both the classroom and a community dance setting. Students require their teachers to have both credibility and authenticity, “students define credibility as the perception that the teacher has something important to offer” (Brookfield, 2006, 67) and they believe that “without authenticity the teacher is seen as potentially a loose cannon, liable to make major changes of direction without prior warning” (Brookfield, 2006, 68).

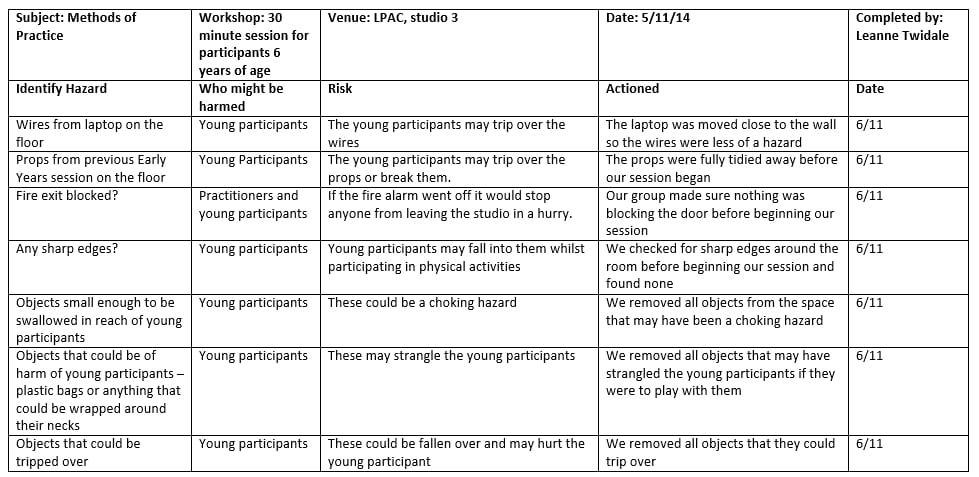

Practitioners who work in community dance will work with various participants of all ages, races, and will work with all genders, with able-bodied and disabled students so it’s important that they understand the different skill sets that are required from them. To work with Early Years participants, the community dance artist must remember to keep a clear voice throughout and not slip into a high-pitched voice when speaking to them. This is because the children are liable to lose interest if there is no authority in the tone of voice. Children are different to other age groups as they have the importance of needing praise after completing every task given to them, “getting praise, or rewards, for specific accomplishments is an important part of building self-esteem” (Greenland, 2002, 91). Relating back to students needing to feel comfortable around their teachers, children will not open up to anyone they don’t trust, “they need to feel safe before they can show you who they are. If children feel accepted without judgement, they are more likely to embody their experience and to share their own meaning for that experience” (Greenland, 2002, 105). Community artists teaching Early Years are also required to join in with the activities they set, this is because the children need to feel trust between themselves and their teacher, as Cheesman points out when working with her participants: “It is important when I teach that the conditions are such that they enable people to take a full and active part in the class” (Cheesman, 2012, 324). Although this isn’t particularly stating that she joins in with her participants during activities, she explains how her participants need to feel comfortable enough within her classes to actively take part. If the teacher refuses to join in with the games, the children will lose any interest and trust in them, however “adults [also] need to know when their support isn’t needed; when to withdraw and let children get on with it for themselves” (Greenland, 2002, 110).

Community dance artists need to plan thoroughly for each session when working with Early Years but also especially when working with disabled students. The practitioner will need to fully understand what activities are appropriate and listen intently to their student’s feedback. Cheesman explains how she worked with disabled students and gained their trust: “Over the eight weeks I kept a journal. Each class was planned taking into account what had transpired in the previous session and input from the participants” (Cheesman, 2011, 32). This is incredibly important when working with disabled participants. A school in Cape Coast, Ghana “offers deaf, blind, and hearing/vision-impaired students the opportunity to learn basic literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving skills” (Hampton, 2013, 39). The teachers at this school must take into account the feedback from their participants to help them feel comfortable, for example, “when the students at Cape Deaf were interviewed, their concerns included their interest in reaching out to hearing individuals to “teach them how to sign so that we can more easily communicate with them”.” (Hampton, 2013, 38). Cheesman also used her participant’s feedback but to help create future workshops as she explains: “The use of feedback / feed forward loops throughout the use of workshops enabled the participants to voice opinions” (Cheesman, 2011, 36). This relates back to students wanting their teacher to be an ally as well as solely a teacher. With the participants feeding back what they liked, disliked and what they would like from future workshops shows that the teacher is committed to making sure the participants are getting the best from the sessions.

As well as being an ally to the students, the teachers also need to have authority to help communicate properly and so that there is a particular order within the sessions. The students need to respect their teachers as well as the teacher respecting them and this must happen within the classroom as “a productive and positive classroom is the result of the teacher’s considering students’ academic as well as social and personal needs” (Stronge et al, 2011, 341). In a school for children with severe disabilities the “parents, teachers, and para-educators alike all spoke of the importance of having well-trained, highly skilled, and knowledgeable staff” (Downing and Peckham-Hardin, 2007, 24). This shows how the teachers are respected by being able to teach the students from experience and their knowledge rather than just being a friend/an ally to their participants.

If the participants within any age group do not feel comfortable throughout the session they will most likely leave having learnt the minimum amount, as well as perhaps feeling worse than when they first arrived. For the teachers to ensure they become both an ally and authority they must plan well and stick to their plans, keep eye contact throughout the sessions and talk in a personal manner so the participants may relate. The teachers must show emotions and be able to improvise around anything that may disrupt the lesson. If the students feel comfortable around the teacher enough there will be a high sense of connection and the work created will be of the best quality.

927 words

Works cited:

Brookfield, S. (2006) The skillful teacher: on trust, technique and responsiveness in the classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cheesman, S. (2012) A dance teacher’s dialogue on working within Disabled/Non-Disabled engagement in Dance. International journal of the Arts in society, 6 (3) 321-330.

Cheesman, S. (2011) Facilitating dance making from a teacher’s perspective within a community integrated dance class. Research in dance education, 12 (1) 29-40.

Downing, J., E. and Peckham-Hardin, K., D. (2007) Inclusive education: what makes it a good education for students with moderate to severe disabilities. Research and practice for persons with severe disabilities, 32 (1) 16-30.

Greenland, P. (2011) Hopping home backwards Body intelligence and movement play. Leeds: Jabadao.

Hampton, T., T., D. (2013) Teaching dance to deaf students: A case study in Cape Coast, Ghana. The journal of physical education, recreation and dance, 84 (7) 35-41.

Stronge, J., H., Ward, T., J. and Grant, L., W. (2011) What makes good teachers good?: A cross-case analysis of the connection between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Journal of teacher education, 62 339-355.